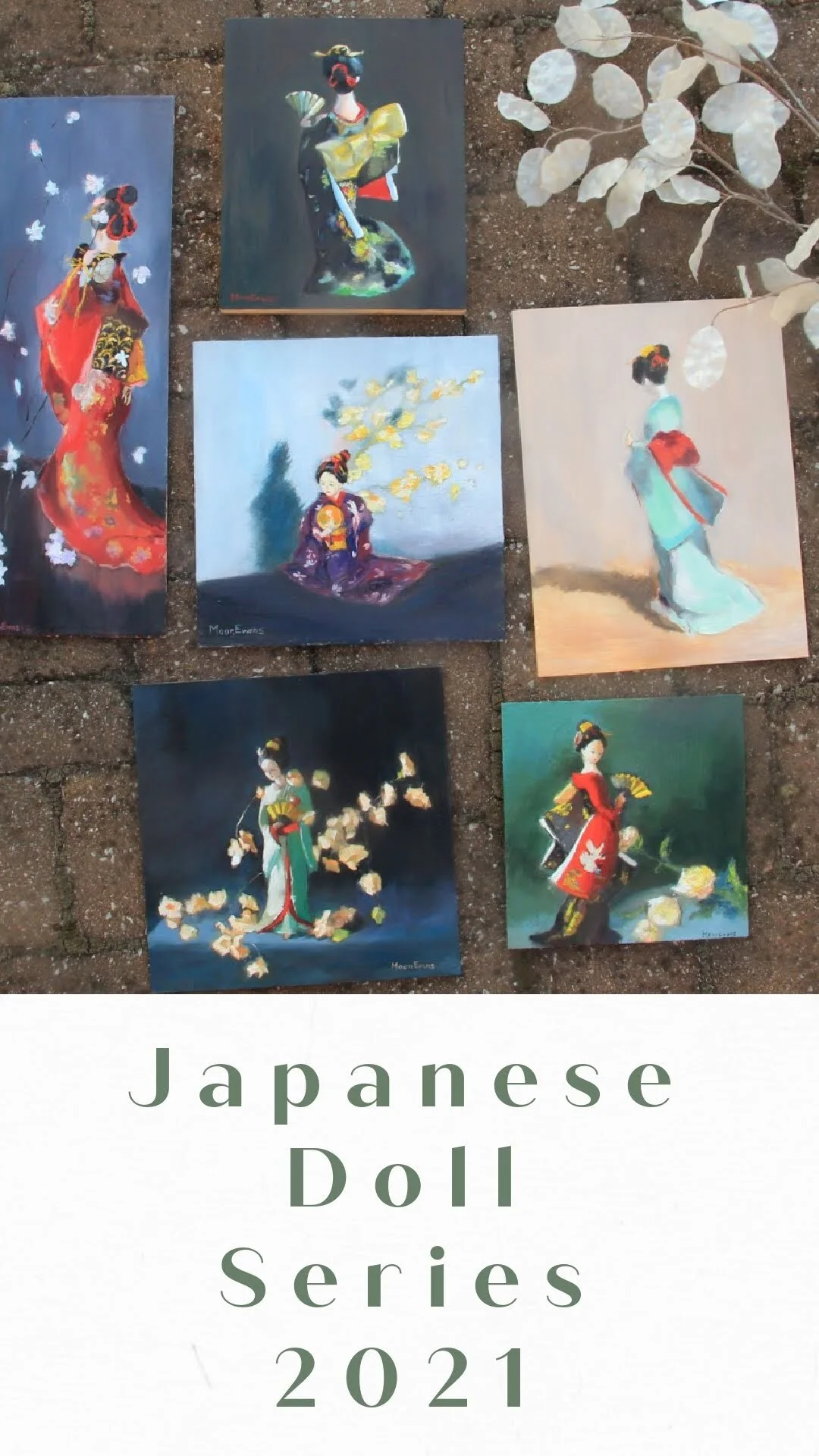

The Story Behind My Japanese Doll Oil Painting Collection: What Beauty Meant in the Heian Period

I'm intensely attracted to the Japanese Heian Period ( running from 794 to 1185 or 1192) culture. Their everyday living is the source of my inspiration in art.

The Story Behind My Japanese Doll Oil Painting Collection: What Beauty Meant in the Heian Period

The Tale of Genji, often regarded as the world’s first novel, offers a glimpse into the aesthetics and cultural ideals of Japan’s Heian Period (794–1185). Reading it gave me a deep appreciation for a very different concept of beauty—one rooted in subtlety, elegance, and restraint.

In the Heian court, aristocratic women of high rank rarely revealed their faces. They sat behind sudare (bamboo blinds), hidden from all but family and close servants. Men would form opinions based on whispered rumors, poetry exchanges, and even just the glimpse of a kimono hem. That mysterious, almost dreamlike distance between men and women inspired how I chose the angles for my Japanese doll paintings—many are shown partially hidden, just like the women of that time.

Heian romances were veiled in darkness—literally. A man might not clearly see a woman’s face until the morning after they’d spent a night together. Physical appearance mattered, but “beauty” encompassed much more: rank, elegance, calligraphy, musical talent, and poetic sensibility were all highly valued.

Obedience and delicacy were also considered beautiful. In Chapter 3 of The Tale of Genji, the character Yūgao is introduced as the kind of woman any Heian man would dream of—graceful, modest, and lacking the pride of high-born ladies. She’s sweet and gullible, traits prized by the aristocracy at the time. It’s a stark contrast to the modern ideal of strong, independent women.

Another telling example is the “Young Murasaki” chapter. Genji encounters a girl living in the mountains, surrounded by serene natural beauty. He falls in love with her purity and innocence—not just her looks. After her grandmother dies, Genji takes her in and personally teaches her poetry, music, and etiquette so she can become the “perfect woman.” This example makes it clear that beauty in the Heian period was something to be cultivated—not something you were simply born with.

Murasaki Shikibu, the novel’s author, had a keen eye for seasonal changes and color harmony in kimono layers. Every combination was carefully considered. Her attention to detail shows a refined aesthetic sense, one that continues to inspire me today—over a thousand years later.

Appearance vs. Personality

This reminds me of a quote from a documentary featuring a Buddhist head nun in Aoyama. When asked about the essence of beauty, she said:

"A woman’s beauty is not about appearance. It’s the personality that seeps from within, like oxidized silver—that’s true beauty. The more you adorn yourself, the more you’re covering up the void."

She had started her practice at age five. Her words stayed with me.

In a way, both the nun’s view and the Heian ideal echo the same truth: beauty is what unfolds quietly over time—through presence, spirit, and subtle grace.